Escritora de cultura, política y relaciones internacionales.

In the celebrated sports movie, Remember the Titans, Denzel Washington played Herman Boone, the real-life high school coach who integrated his school’s football team in Alexandria, Virginia. Though not without its historical inaccuracies, Remember the Titans earned praise for its social commentary on racial justice and brought fame to its setting, TC Williams High School.

Now, local residents and students alike are clamoring to rename that same school after denouncing namesake School Superintendent Thomas Chambliss Williams as an ardent mid-20th-century segregationist.

T.C. Williams High School joins dozens of communities nationwide who have called for institutional name changes because their current namesakes espoused racist beliefs and/or owned slaves. Since the George Floyd protests in May, cities across the United States and abroad have toppled dozens of statues of colonizer officials, Confederate soldiers, and other problematic figures. Top military officers have called for the renaming of military bases named for Confederate soldiers. Even the Washington Redskins, whose owner, Dan Snyder, famously told a USA Today reporter, “We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple. NEVER—you can use caps,» announced on July 13 that they would “retire” the Redskins name. While school name changes have received comparatively less media attention, the cultural significance of this action still looms large.

Take T.C. Williams, for example: as the only high school in the Alexandria Public Schools system, TC Williams houses almost 4,000 students, 78% of whom identify as minorities, according to a U.S. News report. For a student of color to have no choice but to attend a school named for a man who actively discouraged their enrollment takes a psychological toll. “The hurt is still real and there are people –our neighbors — that were directly affected by this,» resident Marc Solomon told a local news outlet after he started a petition and Facebook group to rename the school. «I think it’s wrong to honor this guy.»

A National Movement

According to an Education Week report, over 200 schools across the country carry Confederate names. Many of these schools have largely black student populations. Amerika Blair, a graduate of Robert E. Lee High School in Montgomery, Alabama, and advocate of her school’s name change, told Newsweek, “Knowing that those students have to walk past and celebrate a man basically who did not believe in their basic humanity is very insulting. The name should be changed.»

However, in many places, bureaucratic roadblocks have stalled the name change process. Apart from the standard school board approval required to change a name, certain jurisdictions have imposed further restrictions. For example, the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act bans renaming buildings or monuments older than 40 years old until legislative approval is granted.

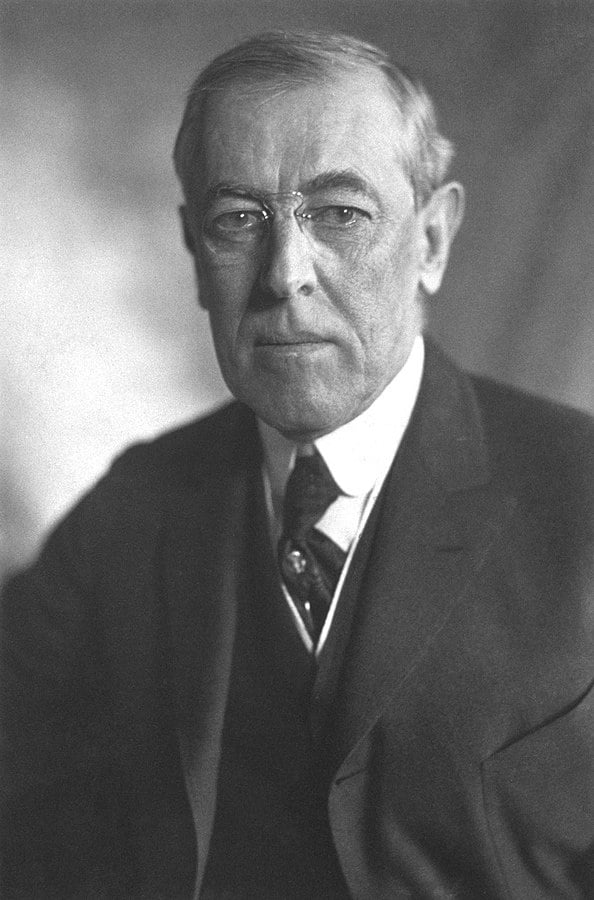

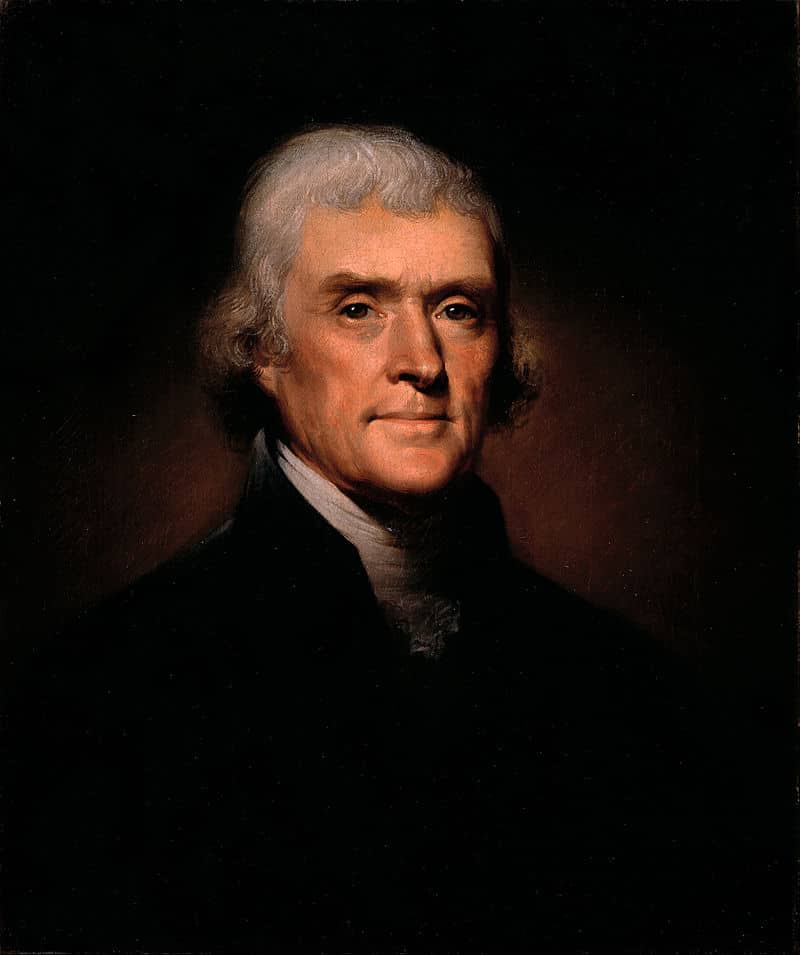

In spite of these obstacles, recent events have galvanized local activists to push for name changes, anyway. From Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs to Berkeley, California’s Jefferson Elementary School, institutions across the country are bucking decades of naming norms in favor of progressive change.

School Names, National Values

School names carry a civic significance that makes their honoring of racist or slave-owning individuals difficult to ignore. In contrast to statues, which could be contextualized or placed in museums next to explanatory plaques, a school named after a segregationist carries an identity in direct conflict with its intended educational purpose. Schools are where we educate students not only in subjects like math and English, but also their civic rights and responsibilities. In that sense, schools disseminate our most fundamental social values. What kind of message are we sending if we name our most crucial and visible establishments after people who promoted inequality and even slavery or genocide?

It’s also high time we start naming public institutions in honor of more women and/or people of color. White men currently make up the vast majority of school namesakes. For instance, of DC’s 200 public schools, over 80% are named for men, and 67% are named for white people. In Philadelphia, out of 345 public or charter schools, just 18 are named for women and 27 are named for people of color compared to 160 named for white people and 193 for men. Only 6 schools are named for women of color. Diversifying those names would be a powerful first step towards honoring our nation’s multicultural society and history.

Of course, it’s not enough just to change the names on the outsides of school buildings. We must also revise our educational curriculum to engage with and analyze our nation’s visceral history of slavery and racial injustice. For guides on how to do this, let’s look to World War II education in modern-day Germany or intercultural bilingual programs in Latin America. These programs, while not without their own flaws, provide useful models on how a nation can address its history of societal racism.

Our culture, learning systems, and values go hand in hand, and we cannot separate one from the other. So if we continue to force minority students to attend institutions that honor racists and slaveowners, then how can we ever claim to be a country of equal opportunity? It’s time we quit honoring segregationists like TC Williams and give institutions the namesakes that students can truly admire and emulate.